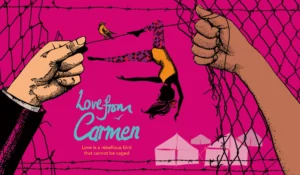

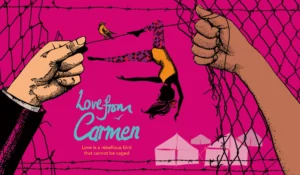

Love from Carmen

Rayne Theatre, Chickenshed

Words by Paul Morrall, music arrangement and direction by Phil Haines

Directed by Cara McInanny

Star rating 4

Rarely have I seen a more energetic show anywhere – ever. Michael Bossisse’s fluid, slick choreography means that the stage, with its huge cast, is never still. This imaginative retake on Bizet’s Carmen is visually like a continuously shaken kaleidoscope and therefore theatrically very exciting.

This is a Carmen for 2024 (Chickenshed’s 50th anniversary year), set in a refugee camp where feelings of antagonism, love and jealousy are running high and the main metaphor for hope is a circus within the camp run by a feisty young woman named Carmen (Bethany Hamlin).

Did I say circus? That means we get, among many other delights, some stunning above-stage ribbon and hoop work, lots of make-you-gasp back flip and somersault sequences and Michael Bossisse (who plays Escamillo very warmly) dancing on jumping stilts. Oh yes, vibrance is the key word here.

Bizet’s music, full of very strong rhythms, lends itself to the drum and bass mix treatment and the words are mostly in rap form – a lot of words, apposite, witty and forthright, and the diction is always clear as principals and narrators drive the plot on at high speed. And that’s my only reservation about Love From Carmen. It’s so intense and complex in concept that the story telling gets blurred. I suspect that anyone who didn’t know the plot of Carmen would have had only the haziest idea of what was going on.

Hamlin is superb. She sings acts and dances (a lot of ballet-inspired work in this production) with all the cocky passion that the role needs – and for good measure gives us a bit of impressive aerial hoop work. Cerys Lambert, who also directs the circus skills, is strong as the contrasting pale, anxious common-sensibe MIcaela and sings beautifully. And there’s lovely work from all the male principals too.

This show uses the usual massive Chickenshed ensemble many of whom sing short numbers – and, as always, you have to be quick to spot who’s actually singing. Occasionally there’s some pleasing harmony work as well. Rarely still, the all singing, all dancing ensemble is impressively managed and includes some very nifty work with wheelchairs and props such as school desks.

I admire very much the way this gloriously inclusive production respects Bizet’s masterpiece but puts a completely fresh spin on it. All the famous earworm melodies are in – complete with all those mixed in additions. And the ending is terrific. We get Bizet’s wonderful, final dark climax music more or less straight and a series of five second blackouts as the story reaches its tragic conclusion. Very powerful indeed.

I was within a hairsbreadth of awarding this magnificent production a fifth star but felt, ultimately that I had to withhold it because of the storytelling flaw. Think of it as four and a half.