A GERSHWIN CELEBRATION with the London Gershwin Players, conductor Mark Forkgen, at the University of Plymouth, part of the Musica Viva Concert Series

Saturday 27 th January 2024

George Gershwin was an extraordinary talent whose music includes many much-loved musical

theatre songs as well as experimental and very assured blends of classical music and jazz. This

concert, though excluding singing, still touched on many well-known sung numbers from his

Broadway hit Girl Crazy as well as from his opera Porgy and Bess. By referencing both areas of his

main work the audience were treated to a panorama of his melodic and rhythmic gifts and

marvelled at an extraordinarily large repertoire, considering the composer died of a brain tumour at

only thirty-eight.

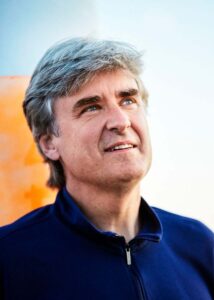

As always with the Musica Viva series, Robert Taub, the Director of Music at the University

of Plymouth, introduced the audience, in his half-hour introduction, to interesting facts and

demonstrations of some of the musical motifs to listen out for during the evening. This time he was

helped by his friend, Mark Forkgen, no stranger to the Musica Viva concerts himself and tonight's

conductor. There is something very warm and open about Forkgen’s conducting style which I always enjoy.

The evening started with the Overture to the musical Girl Crazy, jam-packed with

memorable tunes. Originally these would have been sung [though admittedly not in the

overture!]and Gershwin was lucky to be in partnership with his brother Ira, who wrote all the witty,

clever lyrics for each of those melodies. After Girl Crazy the pair wrote many more songs for other

shows and reviews, many of which have become jazz standards ever since. Such famous numbers as

“My Time”, “But Not For Me”, “Embraceable You” and “I Got Rhythm” feature in this overture, the

musicians moving from faster to slower tunes via a busy musical link, similar to some of the links

Gershwin uses in An American in Paris.

After this smorgasbord of tunes the next offering was the rightly famous and much-loved

Rhapsody in Blue. Here, as Robert Taub explained, they had pared the number of instruments down

to reflect how the original version was, before it became picked up by large symphonic orchestras.

The result is crisper and clearer. Taub was the pianist for this. Having watched him perform before, I

always enjoy watching how he builds a mental space around himself, a palpable concentration, his

hands resting quietly on his lap, before beginning.

I found this less-encumbered version far preferable, though who cannot greet that opening

swoop of the clarinet and its response from the brass section with an answering joy, whichever

version you listen to? What follows is a series of changes of mood and tempo, often which suggest a

story, often busy with the suggestion of hurrying crowds or traffic, as in the last piece of the evening.

In the long piano solo section, I found myself conjuring up a young girl, questing, stopping

and starting, uncertain of her allure, looking round her before gradually gaining confidence. And yet

the title of the piece suggests there is a sad undertone, so that when the orchestra returns it is in a

more reflective mood, at peace with itself. It suggests a night life, tired and packing up. Then

different characters emerge – little pockets of life suggested by the speeding up of the music – which

join at the end into one final triumphant dance of the city inhabitants.

After the interval comes the Porgy and Bess Fantasy, an arrangement made by Iain Farrington, who

played the piano for both these last pieces, which incorporates many of the best-loved tunes from

the opera. As with all his music, Gershwin was breaking new boundaries here, not only by writing an

opera about black Americans from Charleston, South Carolina, but also by using the rhythms of

folksongs and spirituals. He called it an American Folk Opera. Far from the classical structures and

characters that are usual, here we have a street beggar – Porgy – who (and here the theme is as

grand as any Grand Opera) seeks to rescue the girl he comes to love, Bess, from a violent and jealous

lover. The fact that she is also targeted by a seedy, snappy drug-dealer offers us a realer, grimmer

storyline.

The music is full of ominous rhythms and swooping strings or xylophone with subterranean

strings which build excitement and tension and set the atmosphere. The beautiful, famous

Summertime lifts itself out of this 'waiting' mood of piano, sombre cellos and double bass, with their repeated notes. Summertime is sung by the First Violin alone, against a soft background of the

other strings. You can almost hear the chirping of the crickets in the heat.

The storm is wonderfully built – a lightning flash of flute followed by a threatening thunder

of timpani. The African drums, also used, build up to a galloping rhythm against the suggestion of

rain from xylophone. This was a colourful and very successful depiction of a storm. Soon a lazy,

drunken lurching rhythm follows, as if of someone being blown by the wind and trying to keep

balance. Behind are the last defiant rumbles and slides of the vanishing storm before the chirpier

rhythm asserts itself.

Throughout this extraordinary tapestry of music, pieces of well-known tunes surface: not

only “Summertime” but also I Got “Plenty” and “It ain’t Necessarily So.”

Finally came An American in Paris. Through this we follow a tourist, jauntily enjoying his

walk through the French capital. He sets out at a fine pace. Sometimes he stops to admire a vista, a

glimpse through a side-alley. At other times he has to negotiate roads, the terrifying hooting traffic

of Paris. Gershwin is particularly brilliant at suggesting busy city life. It is so vital and vivid that you

can almost see and smell it and you can certainly feel the tourist’s enjoyment as well as his

occasional bewilderment, reflected in the changing tempos. Sometimes the rhythms cross and re-

cross, as if others in more of a hurry than himself, are cutting across him, overtaking, getting

impatient. Gradually we feel him becoming more confident, the music expands as he enjoys a

particular moment, but again and again the mayhem of the traffic returns. Oh, Paris! Can’t you just

feel yourself there as you listen?

So this was a joyful, exciting concert, full of energy, contrast and precision. Thank you to all

the musicians involved and to Musica Viva.