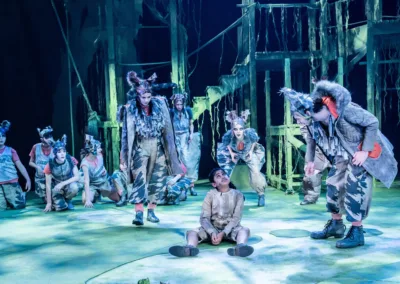

Show: A Christmas Carol – As told by Jacob Marley (Deceased)

Society: London (professional shows)

Venue: White Bear Theatre. 138 Kennington Park Road, London SE11 4DJ

Credits: ADAPTED BY James Hyland from the book by Charles Dickens. Produced by Brother Wolf

A Christmas Carol – As told by Jacob Marley (Deceased)

4 stars

James Hyland is a powerfully talented actor and this is a strong and original way in to this familiar seasonal tale of redemption.

Hyland shuffles painfully in, grunting, sighing, groaning and panting. He is master both of evocative sounds and mime. He looks terrifying in dusty grey make-up ( designed by Nicki Martin-Harper) with red eyes and mouth cutting menacingly through it. Eventually he manages to shed his chains and tells us how he has came back from the dead to shake up his former business partner, Ebenezer Scrooge.

The story which follows is, inevitably, pared down and some of the detail cut because this show runs just 75 minutes. Hyland jumps (often literally) from one role to another and his voice work is splendid. He uses fortissimo partrician for Marley but gives us a whole range of others for the Cratchets, Scrooge’s nephew, the people in the pub and so on. His female voices are particularly effective.

I have seen this show before: it’s one of several interesting, worthwhile one-man shows which Hyland does through his company, Brother Wolf. Last time, however, it was on a conventional stage so that there was definite fourth wall. It works especially well in the intimacy of the White Bear theatre with seating on two sides and no member of the audience more than a few feet away. It means he can pretend that we’re all guests at Mr Fezziwig’s party and that he is sometimes speaking direct to someone on the front row.

It’s an intensely compelling performance.