A friend of mine often mentions William Golding (1911-1993) because he taught her late husband English at Bishop Wordsworth’s School in Salisbury. Then came the enormous success of Lord of the Flies (1954) which allowed Golding to quit the classroom in 1956.

One presumes that the Salisbury years led to much reflection on the cathedral’s 404 foot spire. It’s been the tallest church spire in Britain since 1561 when the spire of Old St Pauls fell in a fire (to be followed by the rest of the building in the Great Fire of 1666) which was said to be 489 feet tall. For comparison and context, the Shard in London today stands at 1004 feet.

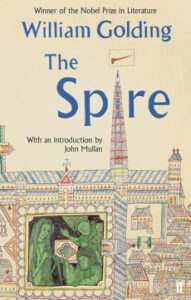

Salisbury Cathedral’s spire was added in 1320 to a building dating from a century earlier. And it’s the logistics of that grandiose extension which form the starting point for Golding’s 1964 novel The Spire, although we’re in an unnamed city rather than Salisbury specifically.

Jocelin is Dean of the Cathedral and hell-bent (literally – he’s deeply troubled) on an absurdly high spire – against the practical advice of the masterbuilder Roger Mason who argues that the foundations, such as they are, will not take the weight.

Golding was a visionary and so is Jocelin who sees “his” spire as a monument to his life and to God. He hallucinates and has erotic dreams as he shifts between everyday life including mundane interaction with others and intense other-worldly experience. He’s a monk, of course, and in 1320 the church was still Catholic. At one point he faces a formal Visitor from Rome to question his actions in a quasi-trial. Eventually we realise that Jocelin is ill – with, one presumes, some sort of agonising spinal cancer. It is eventually described as “a consumption of the spine and back”. “Holy Mother of God. Look at his back!” one onlooker cries when he collapses helpless in the street towards the end of the novel and his robe flaps up. He believes there is an angel on his back, mostly benignly protective but who eventually beats him with a flail – as he tries, racked with guilt, to interpret his pain.

Golding was among many other things a symbolist and, like Lord of the Flies, this novel is full of symbolism. The spire itself, as it grows and thrusts upwards, is clearly phallic and represents Jocelin’s thwarted, convoluted, complex desires. Golding himself, who drafted this novel in an astonishing fourteen days, joked that he was going to call it “An Erection at Barchester.” The young woman, Goody Pangall (her very name is significant) who dies in childbirth has oft-mentioned red hair. Then there’s the “singing” of the stones and pillars in the wind as the building gains height.

It’s a densely, intensely written novel with much metaphysical meandering. It’s also strong on the physical level. Golding has extraordinary powers of observation and description: “Presently ropes began to hang down from the broken vault over the crossways, and stayed there swinging, as it the building sweating now with damp, inside as well as out, had began to grown some sort of gigantic moss” or “Her eyes were two black patches in her winter pallor.” It’s written in the third person but presented from Jocelin’s point of view.

He has a highly informed and very impressive grasp of architectural principles and mechanics too. From my first reading of this book back at college in the 1960s to revisiting it now, I emerged understanding a lot more than when I started, about structural octagons, capstones, supporting steel bands, wind resistance and the like. I also had to manage my own fear of heights because some of the description of experience at the top of the spire is vertiginously graphic.

And of course Jocelin, who believes passionately in miracles, gets the one he wanted. Salisbury Cathedral’s spire is still pointing proudly (reverently?) to the sky 700 years after it was built.

William Golding, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1983. Although it was an honour conferred on, among others, Rudyard Kipling (1907) John Galsworthy (1932) and TS Eliot (1948) it is surprising just how few British writers have achieved this.

Next week on Susan’s Bookshelves: The Faber Book of Christmas edited by Simon Rae