National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine

Conductor: Volodymyr Sirenko

Pianist: Antonii Baryshevskyi

Fairfield Halls, Croydon

18 Ocotber 2023

This orchestra must be supported on its UK tour, I reasoned. So I gave up my regular Wednesday night (musical) commitment and took myself to Croydon. Clearly, many people agreed with me. There were audience members dressed in blue and yellow and, delightfully, lots of children – all silently rapt.

The NSOU’s style is distinctive. They were led formally on to the stage by their leader, Maksym Grinchenko, as the lights dimmed. Second violins sat to the right of the conductor with cellos next to the firsts and the harp at the heart of the orchestra.

This was my first visit to the concert hall at Fairfield Halls (although I’ve been to the Ashcroft Theatre several times) since its long closure and expensive refurb before the pandemic and I have to say that it is now acoustically superb. I should think Volodymyr Sirenko was pleased with the balance he and his band were able to achieve at this rather splendid concert in an outwardly unpromising venue on a wet October night.

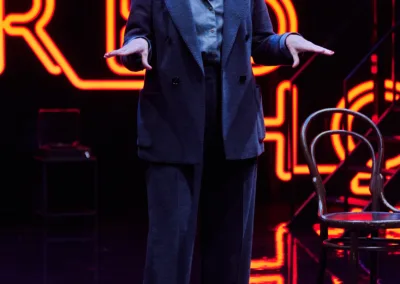

First we got Richard Strauss’s tone poem Don Juan – a big sound and lots of passion with some especially pleasing work from trumpets. Sirenko coaxes effects from his players with his hands and doesn’t use a baton.

I think the fourth is my favourite of all Beethoven’s five piano concerti (although I am inclined to say that of which ever one I happen to be listening to). I love that beautiful piano solo entry which still feels unexpected even when you’ve heard it hundreds of times before. Soloist Antonii Baryshevskyi, who looks like a young Dante Gabriel Rossetti, found aching poignancy, especially in the big runs in the first movement. I was intrigued by the cadenza which was very different from the ones I’m used to. It wasn’t remotely Beethovenian but felt full of anguish until we reached the final trill which triggers the re-entry of the orchestra. I think it was probably a heartfelt political statement and wondered if Baryshevskyi wrote himself in the traditional way. Thereafter came a delicate slow movement, with exceptionally sensitive rapport between the conductor and soloist at every entry and a crisp transition into the Rondo. And I tried not to smile too much at Baryshevskyi’s black jeans, trainers and coloured socks while evey other player was conventionally, formally turned out in black with bow ties for men. His playing more than made up for any sartorial oddity.

The real discovery of the evening, though, came after the interval: the second symphony of Boris Lyatoshynsky, a Ukrainian composer who died in 1968 having, like Shostokovitch, lived and worked for many years under a regime which expected music to be “patriotic” rather than “decadently” experimental. All new music was required to conform to the doctrine of “socialist realism”.

Lyatoshynsky’s work was completely new to me. Dating from 1936 and revised in 1940, the second symphony is a compelling, three movement work of bleak tonality with a lot of angst lurking amongst the rich orchestral colours. Inevitably, it was not approved of and heard very little until the 1960s. The NSOU clearly now plays it as commitedly and knowledgably as the Vienna Philharmonic plays Strauss or the Czech Philharmonic plays Dvorak. It’s in the blood.

I particularly liked the cello solo in the first movement, the soulful brass canon in the third and the grandiloquent, heavy denouement with tubular bells. The NSOU’s double bass section is especially good. Positioned behind the cellos and first violins, they played every note – bowed or pizzicato – with panache and, unusually, it contributed a very vivid part of the texture. I sympathised with Sirenko at the end of the first movement, though – he evidently wanted no applause to break the mood and he was right.

It made sense, although it became a longer-than-average concert, to finish with Finlandia. Yes, it gave the audience something rousing and familiar to go home humming but more importantly it was written as a nationalistic statement in support of the independence movement in Finland. The Fins were resisting the Russians so it’s a good fit for NSOU now. And played with percussion and brass sections as strong as this orchestra has, it sounded incisively powerful.