(A few years ago I was commissioned to write a series of light hearted articles about British icons for an American publication. It then went bust and most of the work was never published. I am therefore dropping them in here on an occasional basis as “Daft Essays” in the hope they might amuse for a few minutes. This one was intended for the publication’s Australian edition)

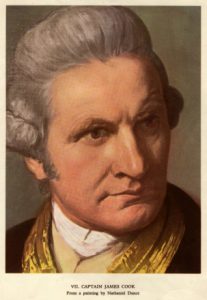

An early look at Cook

It’s a bitterly biting, icy winter’s night in October 1728. And we’re in a

one-up, one-down, earth floored cottage at Marton. Then it was in Cleveland.

Now it’s in North Yorkshire, flexible geography being a British

speciality.

The village lies on the edge of what today’s movers and shakers neatly

parcel up as the ‘North York Moors National Park.’ It’s about ten miles

south of the pretty port of Whitby and it’s one of the coldest spots in

England. If you go there at any time of year, pack plenty of pullies.

Hundreds of miles to the south in London, white-wigged, britches-clad George

II has just become King and is strutting about elegantly enjoying the music

of Mr Handel whose stuff is the Georgian equivalent of top of the pops. But

back in that rush-lit farm worker’s cottage, Grace Cook, formerly Grace Pace

doesn’t, at this moment, care much who’s king. She’s struggling painfully

and laboriously to produce her second son.

Then – a little miracle – against all the odds of poor hygiene, inadequate

diet, cramped conditions and no obstetric care whatsoever, she pops out a

healthy son. He’s named James after his proud Dad and this little lad is

going a long way – in every sense.

Little Jim was one of eight children born to Grace and James, but five of

them died while they were still children. Sad – but not unusual. Then Mr

Cook got an offer of a better job as foreman of Aireyholme Farm at Great

Ayton a few miles to the north. It was a bit of a career break. So the

family decamped.

A bit more money in the coffers meant that James was sent to the village

school (not compulsory in Britain until 1870) so he learned to read and

write – useful skill for a chap who will soon be turning his back on his

chilly origins and navigating his way across the uncharted globe.

But all that’s in the future. For the time being he earned his pocket money

by being a live scarecrow on the farm. That meant spending hours in the

fields frightening peckish birds away from the crops – a common enough

activity for farm children, but educationally developmental it wasn’t.

Young James Cook got his first proper job when he was 17. He went to work ina grocer’s shop at Stathes, a fishing village on the coast, north of Whitby.

Maybe it was seeing the grey North Sea every day, hearing the slap of the

waves on the beach and dreamily watching the ships sail in and out, but

after only a few months James Cook was smitten. ‘I’m determined to go to sea

and seek my fortune,’ he said.

He asked a local family of trading bigwigs, the Walkers, for help. They were

Quakers who took a shine to James Cook’s sober enthusiasm. So they gave him a chance. Thus he learned the craft of sea-faring by sailing in creaky

timber cargo ships up and down the east coast of Britain – mostly carrying

coal from the mine-full North East to London. Imagine George II and his

wife Caroline hosting a ‘do’ in their drafty old Windsor Castle. Perhaps

James Cook has helped to transport the fuel in their fireplaces.

He’d found his metier too. He was rapidly promoted, passed some exams

(see – that schooling was bound to come in useful) and sailed farther field

in Walker ships. ‘I’d like to offer you the command of one of my ships,’ Mr

Walker told the 27-year old James in 1755.

But that wasn’t what this ambitious young man wanted. He had set his sights

on even wider horizons so he volunteered for the Royal Navy. He shone there

too – charting coastal waters, making scientific observations, serving in

North America and taking part in action against the French during the Seven

Years War.

The big break came in 1768 when the Admiralty offered him the command of the Endeavour (built at Whitby) with a mission to sail Tahiti to make

observation of Venus. It was the first of his three great voyages. So,

watch out Australia, the farm boy from Yorkshire is on his way to ‘discover’

you.

He was killed, of course, by frenzied warriors as the result of a bit of

ill-judged, high-handed colonialism against the king of Hawaii in 1779 – not

quite the end his tearful, but joyful, mom might have envisaged for her son

back in that humble cottage in 1728.