I prepared this talk for Bromley u3a Theatre Group in February 2022. A number of people seemed interested when I mentioned it on Twitter etc so I’m sharing the text here for general interest. Of course, I’m willing to do talks for other groups too. Message me if you want to follow that up.

Susan

The Merchant of Venice: An anti-Semitic play or a play about anti-Semitism?

We think that The Merchant of Venice was written between 1596 and 1599 – in the twilight years of Elizabeth’s reign. It was printed in 1600 and so had, one assumes, already been performed by then. The first performance of which reliable records survive was at the Court of King James in the spring of 1605 by which time the new king had arrived from Scotland and been on the throne for two stormy years – the Gunpowder Plot came close to undoing him in the November of 1605. So we are talking about a period of great change as the 16th century gave way to the 17th and Tudors gave way to the Stuarts.

So let’s remind ourselves what happens in this play for anyone who hasn’t read or seen it lately. Antonio, the titular Merchant, borrows 3,000 ducats from a Jewish money lender, Shylock, in order to bankroll a friend in need. The (arguably jokey) deal is that if he defaults, Shylock will be able to claim a pound of Antonio’s flesh. Inevitably Antonio’s ships, and the fortune which depends on them, do not come in on time and Shylock gets his knife out. Then follows the famous court scene which ends in Shylock’s downfall. All this is closely bound up with Antonio’s friend Bassanio who needs money to marry a wealthy heiress (yes – that’s always seemed odd to me too) and the elopement of Shylock’s daughter, Jessica with a Christian.

Every character in this play, except Shylock’s friend Tubal and even he doesn’t come out of it well, is what we would now call strongly anti-Semitic. They all – even his own daughter – loathe Shylock for what he is. The big – and most interesting question – is does Shakespeare loathe him too? I think not.

Our greatest playwright was a lot more nuanced than that. After all he makes Shylock say:

`Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us do we not bleed? If you tickle us shall we not laugh? If you poison us shall we not die?”

… which is a pretty strong plea for what we would now call racial equality.

On the other hand Shakespeare probably didn’t know many – or any – Jews personally. The 2000 or so Jews who were living in England in the 13th century were exiled by Royal Decree issued by Edward 1 in 1290. Not until Oliver Cromwell changed the law in 1656 were Jews permitted to live, and freely practise their faith in England – and that was 40 years after Shakespeare’s death.

As far as we know, Shakespeare never went abroad either but there’s always the mystery of the 7 lost years. Shakespeare’s presence is recorded at the baptism of his twins in Stratford in 1585. He then disappears from all forms of historical record until he turns up in London as a jobbing playwright in 1592. Where did he go and what was he doing? We shall probably never know. Some scholars argue that he might have gone abroad and served as a mercenary- which would explain his in-depth understanding of soldiers, armies and battles. Perhaps he passed through Venice – where the original Jewish ghetto was. Maybe he met some Jews. Or maybe he was just holed up quietly in some garret in, say, Staines or Chelmsford – or Bromley! – reading books about all the places and situations he later wrote about.

Of course, Shylock is no paragon but I think like another of Shakepeare’s tragic figures, King Lear, Shylock is more sinned against than sinning. I’ll return to that shortly.

“Racist” is very much a 20th/21st century term but there are plenty of them in this play and Shakespeare makes absolutely sure you notice their behaviour – with disdain.

Take Portia who’s obliged to marry a man of her late father’s choice through a fairy-tale like lottery of choosing the right one of three caskets. The Prince of Morocco knows what he’s up against. The first thing he says is “Mislike me not for my complexion”. When he, inevitably, picks the “wrong” one. Portia comments “A gentle riddance – draw the curtains, go / Let all of his complexion choose me so”. So much for tolerance and acceptance. It’s so stark I can’t believe thoughtful, perceptive Shakespeare actually approved of such an attitude. He would have certainly have encountered people of colour of the streets of London – by 1600 there were more of them around than many people now realise.

Then there’s Antonio’s anti-Semitism which is astonishing under the circumstances, He’s asking Shylock for a favour. Shylock quite mildly lists some of the insults he has received from Antonio in the past. “You call me misbeliever, cut-throat dog / And spet upon my Jewish gabardine/And all for the use of that which is mine own” he says. You’d expect Antonio to back down and mutter something conciliatory. Instead he snarls : “I am like to call thee so again/To spet on thee again. To spurn thee too.” The sense of overbearing superiority is revolting and I know which of these two men I’d rather have a cup of tea with … Incidentally, notice too how Shakespeare subtly reinforces that point. Antonio is using the familiar “thou” pronoun ( a leftover from the French which merged with English after the Norman Conquest) Here it’s patronising overfamiliarity. Shylock uses the more formal “you” when he speaks to Antonio.

New production opening at Shakespeare’s Globe in March 2022

Or what about Jessica who is, I would argue, one of the most unpleasant people in this play. She clearly has no love, loyalty or respect for her father and his Judaism at all. She has, somehow, met Lorenzo before the play opens and decided he is the ticket to the freedom she clearly craves. She abuses her father’s trust – when he leaves her in charge of his keys – steals jewels and money and leaves. Lorenzo is, apparently, delighted with the loot. What happened to the eighth commandment “Thou shalt not steal” which applies to both Jews and Christians? One of the most heartbreaking lines in the play comes when Shylock is told that Jessica is racing round Europe throwing his money about. She has apparently exchanged a ring for a monkey. “It was my turquoise. I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor. I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys” weeps her anguished father. Did Jessica actually know this was her father’s engagement ring and treasured for its great sentimental value? One hopes not but I’m not holding my breath. Arguably Jessica is a worse anti-Semite than most of the others despite having been born into and brought up in Jewish family.

So how do you interpret this on stage because there’s much about Shylock to dislike too? The pound of flesh proposal is repugnant by any standards, irrespective of race and/or religion, although one wonders how serious it is when it’s first proposed. Antonio is a prosperous man and the chance of all his ships miscarrying at once is very slight. It is only when the ships do not come in (actually they do eventually but it looks as if they’re all lost when the money is needed critically) that Shylock realises he’s on to something. And he’s goaded into revengeful madness by the desertion of Jessica and the sense that the whole world is now against him. Even his servant Lancelot has waltzed off to work for the newly enriched Bassanio because the uniform and conditions of service look better. Shylock is alone, bitter, hurt, outraged and doesn’t Judaism teach “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”? Revenge is about the only thing this beleaguered man has left – and by the time Portia has finished with him in court he has absolutely nothing. He is penniless and stripped of his religious and racial identity- to the glee of everyone else.

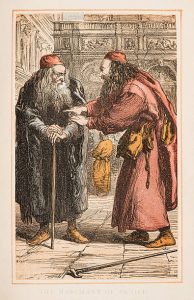

The Merchant of Venice by Shakespeare engraving 1870

When you teach this play to young people, as I have done many times, there is a problem with the word Christian. It’s a slippery word. In Shakespeare’s day and play it means anyone who is not Jewish, Muslim or anyone else who is not signed up to the Church. Note the unequivocal language. “But who comes here? Lorenzo and his infidel” says Gratiano cheerfully when he and Nerrisa have just announced their engagement. The Book of Common Prayer used in the reformed Anglican churches included a Collect for Good Friday which prayed for “Jews, Turks and Infidels”. Christianity was a cultural assumption. Atheism was heresy. So everyone in The Merchant of Venice is “Christian” except Shylock, Tubal and Jessica until she converts and marries Lorenzo. That’s a very far cry from the kindness, humility and deep seated conviction about the divinity of Christ which modern teenagers – and to an extent the rest of us – associate with Christianity today.

Traditionally Jewishness was symbolised by circumcision and Christianity by baptism. Just what and where is Shylock proposing to cut when he brandishes and sharpens that knife in court? For decades, from when I first read the play in school at about age 12, I assumed it was Antonio’s heart as Shylock hints in the court scene. In recent years I’ve realised that it might not be. There are several references in the play to “flesh” which in Elizabethan English – and in Shakespeare – was often a euphemism for penis. And the worst part of Shylock’s punishment and downfall is that he is “condemned” to be baptised. In other words his Jewish identity is to be erased – another tricky thing to explain to 21st century young people who can’t quite see how you can be baptised against your will.

As in most of Shakespeare’s plays the plot is not, for the most part, original. A lot of it came from Silvayn’s The Orator and other contemporary or earlier texts – written during eras when Jews were either outlawed or ghettoised in most of Europe. The most famous ghetto – the one from which we derive the word – was in Venice which we assume Shakespeare knew about. Not that the setting is very Italian – apart from careful references to the Rialto and one of two other things, we could just as easily be in London although – as we’ve seen, Shylock would not have been able to work openly as a money lender in London at this date.

It used to be all too easy – given the cultural disapproval – to stereotype Jews throughout the centuries. Mendelssohn’s father converted with his family in 1822 and his son Felix was baptised at age 7 – this so that they’d have better opportunities. And it’s worth rereading Oliver Twist published in 1838. Fagin, thief, exploiter of children and maybe paedophile is a relentlessly foul character. Look at the original illustrations by George Cruikshank which depict him as a hook-nosed villain. Do not be distracted by Lionel Blair’s musical and film Oliver! which is a distinctly sanitised and saccharine 1968 take on it.

Gradually actors – especially Charles Macready (1793-1873) – began to soften the edges of Shylock, reading the text for its ambiguities. And, this continued during the 20th century particularly after 1945 for obvious reasons

The key point is that The Merchant of Venice is a play not a novel. In a sense it doesn’t exist at all until a director and group of actors bring it to life. Like all plays it’s meant to be interpreted – unlike novels which communicate via hotline from say, the Dickens brain to the Elkin brain. So the honest answer to the question I used to title this talk is actually: That depends entirely in how the director and actors choose to present it. And of course, there are many ways of doing it. Bear in mind too that it’s very rare to see an uncut Shakespeare play these days. Most directors cut quite substantially – which means they can cut the bits which don’t quite suit their interpretation. And they often alter the order of scenes as well as choosing a setting which is, more often than not, a very long way from Elizabethan England or even Venice. I have no problem with any of that. I’m merely pointing out that a production’s emphasis depends on many directorial decisions.

I’ve seen many productions of The Merchant of Venice over the years and I’ve never seen one which didn’t make me loathe most of the non-Jews and feel a lot of sympathy for Shylock. As far back as 1970 for example, Jonathan Miller directed it at The Old Vic with Laurence Olivier as Shylock. Talking of cuts, Old Gobbo’s comic moment was omitted. Presumably Miller thought it trivialised the seriousness of the play which is certainly no comedy in the modern sense. That production was later filmed. At the end we see Jessica – maybe feeling remorse – as the Jewish mourning prayer The Kaddish sounds compellingly over the soundtrack.

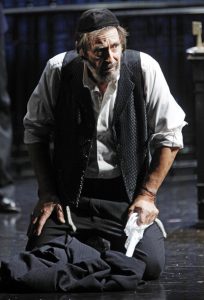

The BBC filmed every Shakespeare play in the 1980s – not always successfully – but I’ve long been haunted by the memory of Warren Mitchell as Shylock, helpless and forced to his knees by hideously, gleefully violent Christians. Henry Goodman played Shylock (directed by Trevor Nunn) at National Theatre in 1999 (that too was later filmed). This time the setting was a 20th century office block where Shylock endured a very moving unseating. And Antony Sher, for RSC in 1987/8 was rivetingly charismatic. Dustin Hoffman did it very sympathetically in The Peter Hall Company at Phoenix Theatre in London in 1989 as did Al Pacino in Michael Radford’s 2004 film.

Al Palcino as Shylock

But oddly, the most interesting and most moving take on The Merchant of Venice I’ve seen in recent years was an unassuming amateur production at Tower Theatre in Stoke Newington last autumn. Set firmly in 1930s Italy it opened with Fascist soldiers marching menacingly, had all the gossipy minor characters sipping espressos and staged wealthy Portia’s opening scene with Nerissa in a spa. At the very end, after the trial scene, and the gentle waltzing of three happy couples off to bed and a glimpse of Antonio as a solitary, lonely figure there was a very brief blackout. Then – lights up and we saw Shylock sitting on a suitcase with the sound of a train. Wow! I thought it was an extraordinarily powerful ending which told another complete story in just a few seconds. It got the production a fourth star in my review.

Just as I was adding my final notes to this talk actor Juliet Stephenson said in an interview that she thought some Shakespeare plays should be laid to rest because they deal with topics which are no longer acceptable. She was actually talking about the misogyny in The Taming of the Shrew but mentioned the anti-Semitism in The Merchant of Venice in passing. Well, sorry, Juliet but I think you’re completely wrong. Art can and does explore unpleasant things and expose them for what they are – and that’s what, I think a good production of The Merchant of Venice does. After all I don’t approve, obviously, of murder, kidnapping and extortion but it doesn’t stop me watching and enjoying TV crime dramas. If you took Ms Stephenson’s view to its logical extent you wouldn’t do most of Shakespeare actually: A Midsummer Night’s Dream features drugging people against their will, Macbeth is about regicide, King Lear includes torturers and Othello a lot of racism … and so on.

Judi Dench is on record as saying that she dislikes The Merchant of Venice because all there are no fully likeable characters. And I can see where she’s coming from. They are all on the make – except poor Old Gobbo, whose son gulls him in a scene which is often cut. But, in my view that’s no reason for ignoring them.

Shockingly, anti-Semitism has never gone away – look at the problems in the Labour party a couple of years ago. So we must resist it and we won’t do that unless we confront it. And The Merchant of Venice is not a bad place to start.