Well it’s always been controversial. Nabokov’s famous 1955 story about a middle aged man’s obsession with pubescent or pre-pubescent girls was turned down by several publishers who, presumably, wouldn’t touch the subject matter. Amongst the ignorant, crass teenagers I mixed with in my youth it was bandied about gleefully as a “dirty” book so of course I read it eagerly but was disappointed. It’s a complex, highly literary work and, with hindsight, at 15 or whatever I wouldn’t have understood it on any level.

Humbert Humbert – his double name mirroring his duallty – is a self confessed paedophile. He refers openly to his pederosis. His narrative is presented as a memoir to be presented in court so the reader knows almost from page 1 that he doesn’t escape his fate although the crime isn’t actually the one the reader long assumes. He’s a scholar and linguist so his testimony is shot through with understated references and word play. Rereading it now, I ache to share it with an A level class so that we could unravel it together. No 21st century examining board is likely to set it, though.

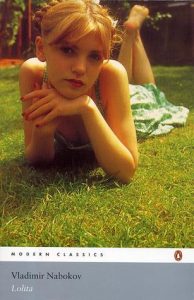

Humbert courts and marries Charlotte Haze because he wants her daughter – the titular Lolita, whose real name is Dolores. After Charlotte’s death he takes Lolita on a year-long motel tour of America, requiring sex from her constantly and getting it with various degrees of un/willingness. His “nymphet”, aged 12 at the start, ricochets from being a child who wants ice cream soda in every drugstore to a young woman experimenting with her own sexuality and power – and back again, many times. There’s nothing straightforward about her.

The descriptions of his lust are utterly revolting – as the narrator knows they will be as he recounts in immense detail what he calls “my miserable story”. In some ways he’s the classic unreliable narrator but in other ways his account is searingly, disturbingly reliable – unless we are to suppose that he’s fantasising when he he tells us – in his wordy way – that, for example, he performed cunnilingus on his “pubescent concubine” before calling the medical services when she was taken ill. Within the confines of the novel I think he’s telling the truth because he is obsessed (and mentally diseased?). One half of him knows that what he is doing is both illegal and immoral – they’re on the run after all – while the other half regards his life with Lolita as perfectly normal which is why he’s explaining it so earnestly.

And that’s the really remarkable thing about this novel – the way Nabokov has got into the mind of this complex character and made him arguably plausible and certainly fascinating. He’s a verbose man too who can casually use words such as “adumbrated” and “viatic” and refer coyly to asking a pre-Lolita target to hold “in her awkward fist the sceptre of my passion” (a reference I would definitely have missed at 15). He often speaks in French too.

The real miracle to me is that Nabokov’s mother tongue was Russian, and English – as with Joseph Conrad – was his second language. His family left Russia when the Bolsheviks seized power and he studied at Trinity College, Cambridge before eventually setting in America. He wrote novels in Russian, published translations and taught Russian literature in universities. His first novel in English – The Real Life of Sebastian Knight – was published in 1941. It stuns me that anyone can have written this startlingly original novel, let alone someone working in a second language.

Next week on Susan’s Bookshelves: Rachel’s Holiday by Marian Keyes