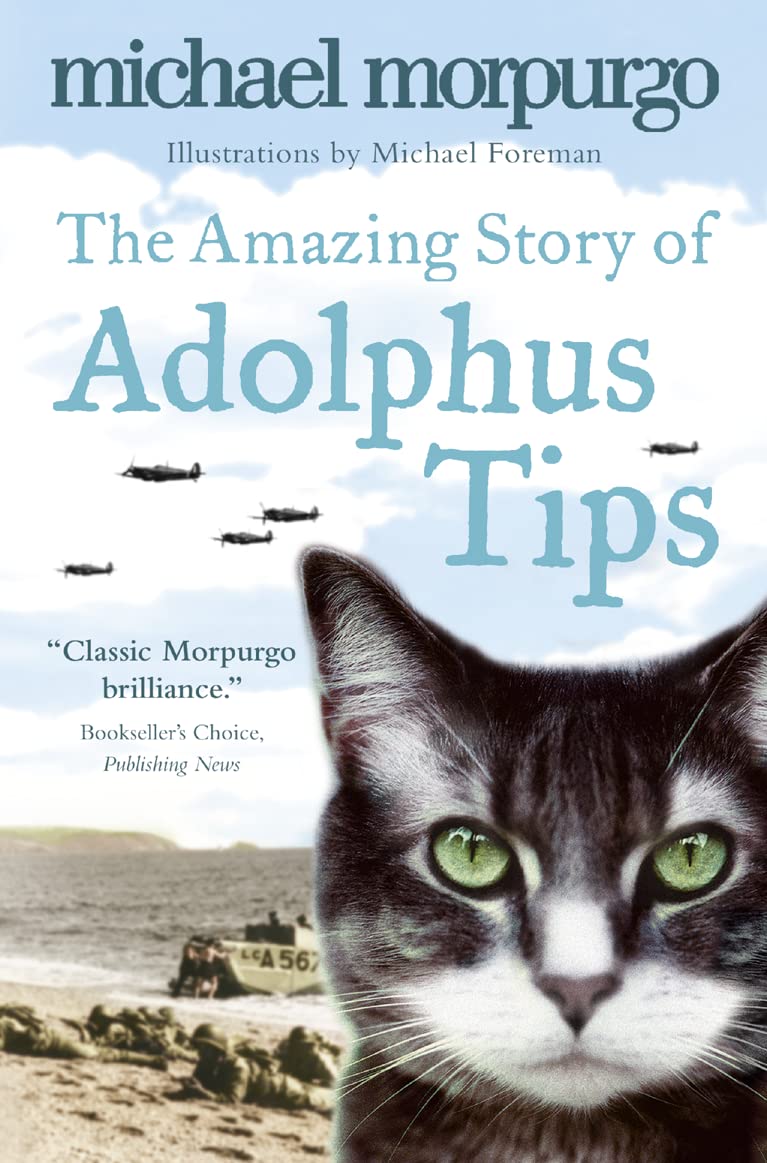

It was a heart-warming pleasure to come back to The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips (2006) There is nothing pretentiously “literary” about Morpurgo’s writing but he knows how to tell a gripping story and he hooks, really hooks, child readers so he gets my vote.

It was a recent conversation with a nine year old which led to my rereading of this title. She told me she likes Morpugo’s stories and had started this one only to have it removed from her by a teacher as “unsuitable”. Her school had apparently badged it as an 11+ title and her parents took the same view. Well, I disapprove with passion of age-labelling. I’d allow (and always did when I had control over such things) any child to read any book on the school library shelves which she or he fancied.

However, just in case I’d missed, or misremembered, something, I wanted to make absolutely sure there is nothing in The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips which could cause distress or offence. And of course there isn’t.

Shot through with Morpurgo’s trademark love of animals and hatred of war, the story opens with a recently widowed grandmother disappearing on a mysterious jaunt. By way of explanation she then sends extracts from her 1943/4 diaries to her grandson who has often stayed with her in Devon. And, obviously, the framing device finally brings us back to the grandson and a Big Reveal about the real reason for Grandma’s trip.

We’re near Slapton Sands, Devon where Lily lives on a farm with her family and cat, Tips, who is purringly, furrily depicted. Her father is away fighting and her mother and grandfather are under pressure. The area is being used as preparation for the D-Day Landings which Morpurgo has researched carefully. This has brought many Americans to the area including Adie and his friend Harry who befriend Lily. Both men, just young conscripts, are black so they widen her horizons simply by being themselves.

Then the area has to be cleared for military use and Lily’s family is temporarily evicted which causes the disappearance of her beloved cat. Yes, there’s sadness and loss in all this: there are U boats out there torpedoing ships after all and, at a different level, how does a farmer deal with continual litters of kittens? There is also warmth as Lily becomes friends with Barry, the evacuee from London, and gradually comes to appreciate her teacher, Mrs Blumfeld, Jewish and from the Netherlands. She is learning about people and situations all the time and the reader learns with her.

War is ugly. It denies happy endings to many people and several characters in this story have to deal with the deaths of people they love. Lily, however, in her old age, having nursed her very sick husband for a long time, finds a new beginning and it’s lump in the throat stuff. So yes, share this with any child you know who wants to read it. Even the publisher suggests age 8-12. If I knew my nine year old acquaintance a little better, I’d buy her a copy and tell her to enjoy it quietly at home without telling anyone at school.

Next week on Susan’s Bookshelves: