Credit Alistair Muir

Last week I went to Open Air Theatre, Regents Park to review the revival of their outstandingly original and moving Peter Pan, predicated on the Lost Boys really being lost ten years later in the trenches. I saw it first in 2014.

It was my first open air production of the season – apart from Much Ado About Nothing at the Globe, part of the Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank series in March but that is really something different. I have dozens more outdoor shows booked in between now and September in various venues: some purpose built and permanent others cheerfully “pop up”.

Well, I wasn’t cold at Regents Park and never have been, even when the conditions are quite chilly, because the auditorium, like the Globe’s “wooden O” is a complete circle and there’s nowhere for the wind to get in. At the Globe I’ve often been damned uncomfortable (oh those backless benches!) but never cold. Nonetheless we routinely pack a rucksack with a rug, scarves and gloves whenever we head off to an outdoor venue because this is Britain and you never know. Even semi-permanent and covered venues such as the pavilion at Wormsley for Garsington Opera or the space used by Opera Holland Park can be jolly nippy.

Attending the first show of 2018 made me wonder, not for the first time, why we mad Brits persist in doing outdoor theatre. This is not Verona, Seville or Avignon, after all. We live in a country which doesn’t seem to have a climate. It just has weather. I suppose staging an outdoor show is a Johnsonian triumph of hope over experience. Dr J was referring to his father’s second marriage but the same principle applies.

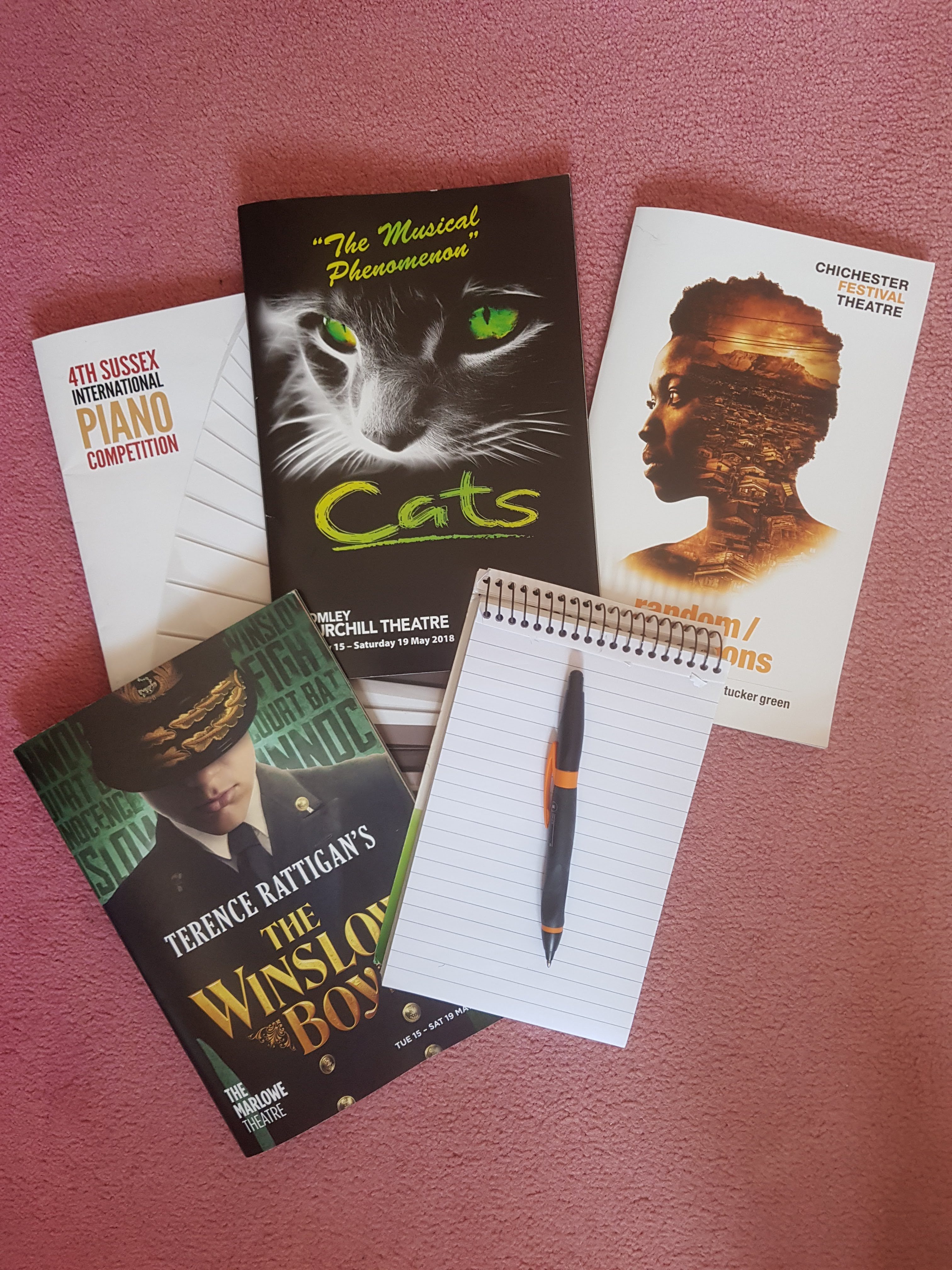

I fondly remember the good times. On a really warm Mediterranean type evening – and it happens three or four times a year if we’re lucky – there is absolutely nothing like a fine open air show. Open Air Theatre, Regents Park is a sort of theatrical paradise when the weather’s right but I also remember arriving there for a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in heavy rain a few years back. They played the first two acts, their trainers audibly squelching. Then rain stopped play when the stage manager aborted the performance for health and safety reasons. The Tempest in a tempest at Mount Ephraim Gardens in Kent stands out in my memory too as does a The Taming of the Shrew at Canterbury when it sheeted all evening. Ever tried making coherent review notes inside one of those polythene bag ponchos? Not easy.

I have also, several times, been so cold at unsheltered pop up open air venues (Leeds Castle, Boughton Monchelsea, Coolings Nursery, and Kensington Gardens among others) that my brain has numbed to such an extent I could think of nothing but getting away and getting warm – even in June or July.

The worst ever was a Christmas show – yes, Christmas so it was December – at Tom Thumb Theatre in Margate. To my amazement most scenes were staged outside. For part of the time it snowed, with the wind howling in from Siberia across the bay. I learned afterwards that the playwright lives in Florida. It presumably didn’t occur to anyone that what works for Christmas in Miami might be less successful in Margate. I was so cold that night that I was still chilled through even after driving 40 miles home with the car heater on full.

So staging outdoor theatre is high risk. And that’s part of the frisson. Neither company nor audience ever quite knows what’s going to happen with the weather or anything else. When I saw a touring production of Hamlet at Groombridge Place near Tonbridge, peacocks shrieking nearby, the set was a cart-size box enclosed at the back and sides like a mini proscenium arch. At about the moment when Hamlet is briefing the players a furry brown alpaca appeared at a gate just to the side and behind the set. Every audience eye swivelled. And there were chuckles. We all knew that none of the actors would be able to see what we were looking at which made the situation even funnier. The beast stood there, apparently enjoying the play, until the interval when a staff member roped it up and led it back to where it was meant to be. Upstaged by an alpaca: it doesn’t happen at National Theatre or in the West End.