I’ve been keen on the operas of WS Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan for most of my life. It began with The Mikado at the school my father was teaching when I was five after which I sang “Tit Willow” as a party piece to anyone who would listen. My sister got the same bug because she grew up in the same household surrounded by G&S LPs. Delightfully my elder son, Lucas, who’s a very competent semi-pro musician on top of the day job, has got it too.

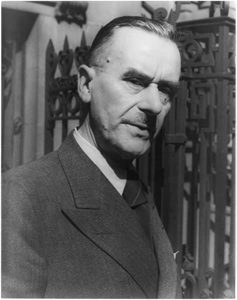

He and I were chatting at his home recently late one evening over a glass of wine after he’d conducted a performance of The Sorcerer in a Cambridgeshire village barn. Somehow we got on to George Grossmith who sang most of the bass baritone roles in the original G&S productions. Martin Savage played him rather well in Mike Leigh’s 1999 film, Topsy Turvey. Lucas has sung most of those parts – often known as the Grossmith roles – too. I’ve seen him as Koko, The Lord Chancellor and all the rest. Well, we agreed that neither of us knew anything about Grossmith beyond his having sung the roles and written a timeless and famous comic novel called The Diary of a Nobody with his brother Weedon. “Surely” I said, reaching for my phone, “Someone must have written a biography?” Indeed someone had: Tony Joseph in 1982. Of course nearly 40 years later it’s out of print but there are plenty of second hand copies available via Amazon. I bought one on the spot.

Born in 1847, Grossmith came from a theatrically inclined family. His father performed as did his grandfather. Young George was clever, funny and well educated. He worked as a journalist (court reporter) before being gradually sucked in to the theatre. He met Gilbert in 1877 who offered him the role of John Wellington Wells in The Sorcerer. He was slight, had impeccable diction, a gift for comedy and an unremarkable singing voice. He found first nights so nerve-wracking that it affected his performance.

He stayed with the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company for seven years, became very famous, made many friends in high places including royalty before branching out on his own. He wrote hundreds of songs the most famous of which is “See Me Dance the Polka” and would do a one man performance from the piano including sketches and songs – he toured Britain and America with these shows and was commercially successful. Meanwhile he had married, was happy and the father of four children, most of whom eventually followed him into the business. Their descendants have many letters and papers which provided much of the source material for Tony Joseph’s book. Although the style is a bit stilted in places it’s very well researched and detailed.

No one really knows how much imput Weedon had in The Diary of a Nobody. He certainly illustrated it. He was a trained artist who could never quite make ends meet commercially so he too, went into stage work. Joseph thinks that even if Weedon didn’t do much of the writing he certainly provided a number of the ideas for the hilariously dead pan doings of Charles Pooter.

Next week on Susan’s Bookshelves: Elizabeth Finch by Julian Barnes