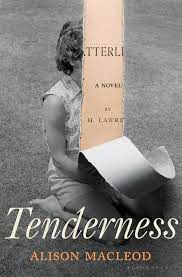

Keen readers of this blog might remember that in September 2021 I wrote about Lady Chatterley’s Lover which I had just reread after many years away from it. Unbeknown to me, Alison Macleod’s novel Tenderness – a magnificently ambitious response to Lawrence, his novel and its long term impact – was published in the same month. It was well reviewed but somehow it didn’t cross my bows and I missed it.

Then came a bit of serendipity. Alison Macleod lives in Brighton where my son Felix did a job in her house last autumn. They got chatting about her work and my interest in Lawrence. Perhaps she was surprised that a jobbing plumber could discuss such things but hey – look who brought him up! Anyway the upshot was a signed copy of this impressive book under the Christmas tree for me in Felix’s house last month. And what a welcome surprise it was.

It’s a historical novel which unfolds in three sections but she plays with chronology and the strands intercut each other. First we meet Lawrence in the 1920s (and before) when the tuberculosis which killed him in 1930 is beginning to bite as he moves, usually impoverished from place to place at the behest of friends. For one summer he and his difficult wife Frieda lived in Sussex as guests of the Mynell family. This is one of the novel’s many “Oh yes, moments” I read Alice Meynell’s poetry when I was doing my MA in 19th century poetry and I knew of her son-in-law Perceval Lucas because he was a collector friend of Cecil Sharp and my parents were keen members of the English Folk Dance and Song Society when I was growing up – the novel is stuffed with such names and connections. Eventually when Lawrence was living in Florence his last novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover was published privately in 1928 – regarded as so obscene in some quarters that it was risky to send it through the post.

The second strand of the novel takes us to the USA where Macleod develops an engaging subplot having discovered that the 1960 obscenity trial was closely followed by J Edward Hoover as head of the FBI. Her fictional interpretation is that he planned to use Jacqueline Kennedy’s “unhealthy” interest in “a dirty book” as a means of scuppering her husband’s election as president that same year. Undercurrents abound as we are led to speculate on the Kennedy marriage, Hoover’s sexuality and much more. It’s fiction but the research is immaculate.

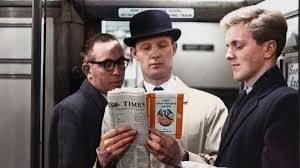

Finally comes a warm and exciting account of the London trial itself – attended, in a sense, by Lawrence’s ghost. Like Macleod, before she began researching Tenderness, I had assumed that Penguin Books went into the trial certain that they’d win, perhaps using it as a way of finally establishing freedom of expression for future books. Not a bit of it. It was, apparently, a nail bitingly close thing with Mervyn Griffith-Jones, for the prosecution, throwing in a sodomy trump card at the eleventh hour. There was even a real fear that Sir Allen Lane, founder and owner of Penguin Books, could be deemed personally responsible and sent to prison. In the event, of course, the jury ignored the summing up and returned a not-guilty verdict thereby changing the course of publishing history.

I enjoyed every word of this 600 page brick of a book. “Tenderness” was Lawrence’s original title for Lady Chatterley’s Lover and of course there’s a great deal of exactly that in both Lawrence’s most famous book and in Macleod’s take on it. Sex between committed adults is a pure expression of feeling and why not use straightforward vocabulary to describe it? Marriage, on the other hand, is often anything but pure as Macleod makes us see again and again whether it’s the strained relationship Lawrence has with Frieda, Connie Chatterley’s marriage to the impotent Sir Clifford or the Kennedy situation in which he is mostly out on the campaign trail and she is elsewhere, pregnant and wondering.

I also fell in love with Macleod’s version of Lawrence himself – gentle, kind and witty despite being misunderstood and ill. This is one of those rare books which made me feel sad and bereft at the end because I’d finished it and would have to move on.

Next week on Susan’s Bookshelves: Brave New World by Aldous Huxley.