Antony Sher is a polymath. He is one of the finest actors in his generation. No one who saw them will ever forget his tensely acrobatic Tamburlaine, his maligned, manic Shylock, his tragically delusional Willy Loman or his vulnerably self-absorbed Falstaff – to mention just a handful from decades of fine work.

Antony Sher is a polymath. He is one of the finest actors in his generation. No one who saw them will ever forget his tensely acrobatic Tamburlaine, his maligned, manic Shylock, his tragically delusional Willy Loman or his vulnerably self-absorbed Falstaff – to mention just a handful from decades of fine work.

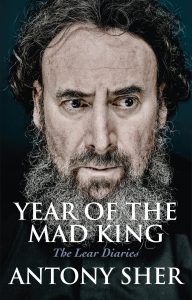

He’s also a respected writer with four books of theatre memoir, an acclaimed autobiography and several plays on his CV. And now comes King Lear and this book … describing his journey from first agreeing to play Shakespeare’s mad king to the opening night at Stratford last year. It is entirely and extensively illustrated by Sher’s own paintings and drawings, mostly of himself and other actors. Yes, he’s an accomplished artist with several prestigious exhibitions behind him too. The images are vibrantly alive with character shining out of each and every one of them.

Like Alan Bennett, Sher is a diarist and that’s where the meat for Year of the Mad King comes from. As he starts to learn the lines (often facing the countryside from the house he shares near Stratford with his partner and director, Gregory Doran but also in Brooklyn and elsewhere) he reflects on the play. Those reflections, observations and thoughts are effectively a King Lear critique so this book is essential reading for anyone studying or trying to make sense of the play. Is Lear suffering from dementia? No. Why does the Fool suddenly disappear? How do you deal with the practical problem of carrying on the dead Cordelia when you have one arm and shoulder which is both painful and useless as Sher has at this time? What should Lear look like? And so on and on.

At another level Sher writes movingly about the non-Lear things which are happening concurrently. He loses both a sister and a sister-in-law during the Lear preparations and his close friend actor/director Richard Wilson has a major heart attack. The distress, shared by the ever-present, practical Greg, is beautifully evoked. At the same time Sher seems to have developed a major hearing problem which specialists prove unable to help with until one puts a spanner in the works with a rather unwelcome suggestion. He writes: “Thought back over the last year. Uncanny. It’s been dominated by preparations for Lear, and characterised by Lear-like obsessions: physical weakness (ailments) and the smell of mortality (death). Real life has certainly provided plentiful research material for playing Lear, but it hasn’t felt useful. Just too close for comfort.”

In the background to all this is the warm, loving, supportive relationship with Greg who manages to run the RSC, to direct King Lear and still have time to photograph a hedgehog in the garden or to cook a lovely meal. Sometimes there’s stress of course, especially when Sher is so concerned about his hearing that he threatens to pull out of Lear. “The private and professional relationships have got impossibly tangled” says Greg at one difficult moment. The reader feels involved and very concerned too.

Of course, they find a way through the problems. “So … we’ve done it. We’ve done King Lear” Greg says after they’ve had slipped away from the first night party, speaking in what Sher describes as “a dazed but joyful way”.

Actually, on balance, I think “polymath” may be too tame a word for Sher’s multifarious creative talents. I think he would have excelled on almost any path he’d chosen – except, by his own admission, music making. This book is a deeply compelling read with an insight in almost every sentence.