I discovered Daphne du Maurier in my mid teens. Rebecca was warmly recommended by my mother who had read it, aged 16, when it was first published in 1938. I lapped it up and went on to read every du Maurier publication I could lay hands on over the next couple of years. And of course Dame Daphne, as she became in 1969, was still very much still alive (she died in 1989) so the novels went on appearing.

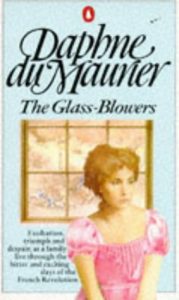

The Glass-Blowers was published in 1963 when I borrowed it eagerly from the library, having as we would say now “pre-ordered” it. I read it again during a family holiday to France when my children were young in 1980.

Realising recently that I hadn’t reread any du Maurier for a while I looked at her long, varied list and decided that I wouldn’t, for once, go for the more obvious options. All I could remember about The Glass-Blowers was that is about… err… glass-blowers. So it seemed a good moment to revisit it.

It is a historical novel, set late in eighteenth and early nineteenth century France. Glass production was a thriving industry, led by hardworking, hands-on family dynasties who worked with communities of families living in tied accommodation around the foundry. Then politics and revolution changed everything for ever.

This is one of several du Maurier novels and non-fiction works centred on her own ancestors. Mary Anne (1954) and The du Mauriers (1937) are other examples. She dedicates The Glass-Blowers to “my forebears, the master glassblowers of La Brûlonnerie, Chérigny, La Pierre and le Chesne-Bidault.” Narrated by the elderly Sophie Duval, the story focuses on her brother Robert who loses everything several times and doesn’t tell the truth – and yet he is charming, kind and charismatic along with his many faults and flaws. It’s a strong, compelling plot full of characters you are really interested in – this is du Maurier after all. She does the paths of Sophie’s other brothers, Pierre and Michel especially well, for example. I love, as ever, the sweep down the decades that du Maurier is so good at.

The Glass-Blowers is also worth reading for two other reasons. As I used to tell my students almost every day – there’s a huge amount of information in novels. That’s why people who read fiction know things. First, The Glass-Blowers gives an informative and colourful glimpse into the world of glassblowing – just how skilled it is and how much practice it takes to get it right. Most glassblowers, however, eventually succumbed to a fatal lung disease because of the glass dust – presumably a form of cancer like mesothelioma which is caused by asbestos.

Second, this is a very evocative French Revolution novel. It’s not about heads rolling away from the guillotine or aristocracy running away – although such things are mentioned in passing. Underpinning this novel is account of how it felt on the ground when loyalties, philosophies and factions were changing all the time and ordinary people lived in constant fear. They struggled to understand what was going on in a world in which rumour travelled fast but reliable news pretty slowly. Getting to and from England as Robert does is only possible during the brief Peace of Amiens. Bonaparte becomes Emperor and eventually the monarchy is restored. What was it all for? Sophie doesn’t really know.

Next week on Susan’s Bookshelves: Pied Piper by Neville Shute