Coming back to Charlotte Bronte’s life changing, life-affirming 1847 masterpiece for at least the twelfth time is like listening to a Beethoven symphony or gazing at van Gogh’s sunflowers. Every word, note or brushstroke is warmly familiar and yet there are always things to marvel at that you’ve never noticed before.

At one level it’s a rags-to-riches story. Jane, orphaned and unloved is sent away to boarding school and then goes to work as a governess in a rich man’s house. She falls in love with her boss and he with her but there are many complications before they finally find their happy ending. And I think that’s about the baldest, tritest summary I have ever written!

The narrating, eponymous Jane is a prototype feminist. She has no family (or believes she doesn’t) so knows she must take full responsibility for her own life and welfare. Advertising herself for a governess post is, for instance, a pretty radical action for a young woman who has hitherto led a very sheltered life. She comments:

“Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings, knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags.”

Yes, that really was written 176 years ago. And it’s extraordinary to think that in some circles and some parts of the world, not much has changed. Moreover, this is the certainly the sort of thing my grammar school headmistress would have said (and did) in the 1950s and 60s. Look, incidentally, at all those semi-colons – how punctuation habits have changed.

So what sort of people are Jane and Mr Rochester? Well, for a start, neither of them is physically attractive. Jane is plain and very small at a time when statuesque women like Blanche Ingram or even Bertha Mason were admired. Her horrible cousin John Reed describes her as a toad. No one ever calls her pretty and she knows she isn’t. Mr Rochester has a huge head and a jutting brow, as Jane repeatedly tells us. It is their personalities and the chemistry between them, along with mutual respect which drives their burgeoning love – along with their being able to have long, adult intelligent conversations on a completely equal level.

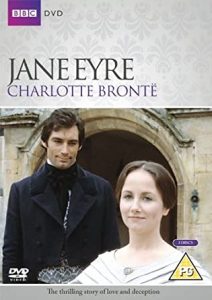

Of course there have been dozens (and dozens) of screen and stage adaptations. For me, the first was the 1956 serialisation on BBC TV (with Stanley Baker and Daphne Slater) when I was still at primary school and it was that which first led me to read an abridged version. But I’ve never seen a dramatisation which does the novel justice. Susannah Yorke and Edward C Scott in the 1970 film were both far too attractive, for example, and the 1983 BBC version with Timothy Dalton as Mr Rochester was a travesty. I’ve never, to be honest, been overly impressed by Dalton as an actor, good looking as he is, and he was certainly miscast for this role.

For me the power (and I still find Jane Eyre a page-turner) is in the words. Volume 2, chapter 8 is pivotal. It’s a hot summer night at dusk. There is tension in the air because of a forthcoming storm. Jane and Mr Rochester are in the garden pretending not to see each other and the way Charlotte Bronte ratchets up the eroticism is masterly.

It is easy to see Mr Rochester as a wicked man (and I think I probably did in youth) who tries to commit bigamy but actually he’s anything but. He could have put his wife, Bertha – who has, in modern terms, a hereditary form of intermittent psychosis which triggers pyromania, nymphomania and violence – into some appalling asylum. Instead he has her cared for at home as decently as he can. She’s locked in but not restrained as she would be in an asylum. Then when the building is on fire he seriously injures himself in trying to rescue her. That said, I always find the way he leads Blanche Ingram on pretty distasteful. She is not a likeable woman but she doesn’t deserve to be deliberately toyed with and used.

Later in the novel Jane is rescued from self-imposed destitution (I’m always irritated with her for leaving her bag on the coach) by the Rivers family. Eventually St John Rivers and his sisters turn out, through one of those glorious Victorian novel coincidences, to be Jane’s cousins: thus she exchanges the broken Reeds for the Rivers of life. Did Bronte actually mean that? Probably – she had to choose names for them after all.

St John Rivers, a clergyman, is in some ways far more of a “monster” than Mr Rochester. And unlike Mr R, he is classically good looking: tall, blonde and personable. He wants to marry Jane, for entirely practical reasons. He wants her to assist him in his overseas missionary work. He has no love for her (in fact he’s in love with someone else and refusing to follow his heart). He is cold and controlling with no respect whatever for Jane’s independence. It’s a fascinating contrast – like so many things in Jane Eyre.

Another thought on rereading this novel now. We’ve just come through a pandemic. I’m struck, as never before, by the casual, habitual bed sharing at Lowood School. Based on the author’s own experiences at Cowan Bridge School where two of her sisters died, the institution is decimated by an epidemic. No one knew about bacteriology until the big break through by Louis Pasteur in 1850. Jane Eyre is a novel of its time.

It’s also very much a novel for now. If you haven’t read it lately then I urge you to do so.

Next week on Susan’s Bookshelves: Stories by Rudyard Kipling