Show: The Boy Who Fell Into A Book

Society: Tower Theatre Company

Venue: Tower Theatre

Credits: Alan Ayckbourn

The Boy Who Fell into a Book

4 stars

Photos: Robert Piwko

Alan Ayckbourn’s 1998 play was written for the ‘Year of Reading’ in 1999. Effectively a witty homage to the power of books, it’s ideal for half term family viewing.

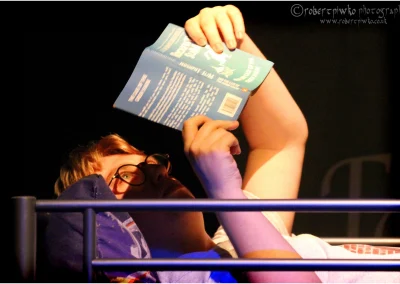

Kevin (James Forth) is an avid reader and we first see him on the top bunk in his bedroom reading a novel about a Los Angeles detective named Rockfist Slim. Then he falls asleep and suddenly he and Rockfist are confronting each other and landing in a series of books (Kidnapped, Beginner’s Guide to Chess and MR James’s ghost stories among others). It’s like The Magic Faraway Tree spliced with the quest element of The Wizard of Oz because Kevin – who is, of course, au fait with every book they arrive in – faces a lot of danger and wants very much to get back to his bedroom. Interesting point of metaphysics: Kevin is at risk from the ubiquitous shape-shifting villainess but all the other characters are invincible and immortal because they’re fictional and will live on in readers’ heads whatever anyone tries to do to them.

All the acting in this production is strong. Forth excels as Kevin, a boy whose head is full of stories. He blinks, challenges, concedes, grows and yet remains convincingly boyish throughout. Cranfield – with great competence – deliberately presents a stereotypical US investigator with a harsh LA accent and an uncompromising line in threats and insults. Initially he’s very hostile to Kevin but the two gradually become buddies resisting a common enemy.

In support of the two of them is a talented four-person ensemble who seamlessly play a whole series of other parts in an impressive range of voices. Lucy Moss, for example, is outstanding as the simpering, lisping Red Riding Hood, Rockfist’s quarry Monique, who is French, and a revoltingly saccharine story teller among other roles.

I should think this cast – and John Chapman, their director – had a lot of fun putting this together – especially the very amusing Woobleys scene in which all the dialogue consists of the word “woobley”, based on a book Kevin’s four year old sister left in his room. It’s a good production.

As for me, Ayckbourn plays seem to be like buses. You don’t see one for ages then two come along at once. This was the second one I’ve seen in nine days. The Boy Who Fell into a Book is, though, in a very different mood form Woman in Mind. What a versatile and prolific playwright Mr Ayckbourn is.

First published by Sardines: https://www.sardinesmagazine.co.uk/review/the-boy-who-fell-into-a-book/

The Famous Five: A New Musical

The Famous Five: A New Musical