Kitty Whately

Neil Balfour (emerging artist)

Anna Tilbrook (piano)

This imaginatively programmed all-American concert moved from Copland and Barber to an entertaining selection of Sondheim moments including several from the titular Into the Woods. Along the way we also got Rogers and Hammerstein, songs by William Bolcom and in the crassly obvious token woman position, one by Margaret Bonds.

Whately, now at the top of her game can do pretty much anything. There was real tenderness, for example, in her rendering of Barber’s Nocturne and Sleep Now – unfussy performances in which she simply stood, sang and let the music do the work. Half an hour later she was bobbing up and down behind the piano for a hilarious series of mini cameos in wigs and furs during Buddy’s Blues.

Billed as an “emerging artist”, Neil Balfour worked adeptly with Whately in several duets as well as delivering a warm account of O What a Beautiful Morning and a very accomplished one of William Bolcom’s Black Max – a compelling minor key swing number which Balfour really made his own.

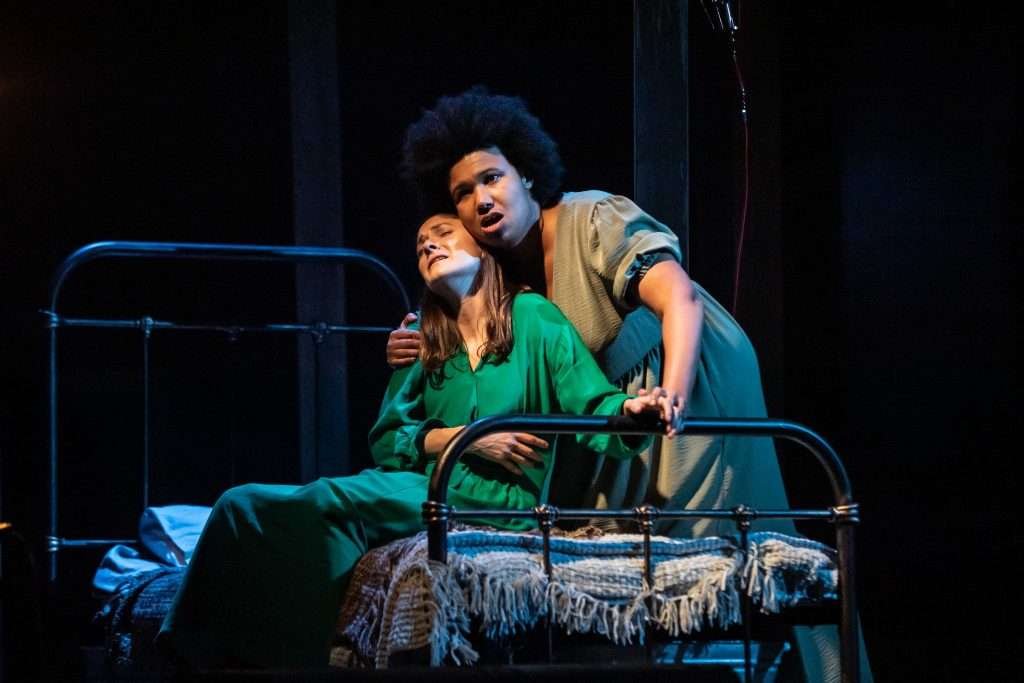

There was lots of chemistry between the two of them in Sunday in the Park with George, which like most Sondheim numbers is quite long and needs careful sustaining and balance. Whately really nailed the model’s frustration and Balfour had Seurat’s irascibilty perfectly. I admired the way Balfour and Whately did Happiness too – with two sets of thoughts going in different directions and then coalescing musically.

The best moments of the evening though were Whately singing Mr Snow from Carousel – all coy, pragmatic love – and her well judged rendering of Could I Leave You in which she makes it clear that yes she could and she isn’t going to miss those “dinners for ten – elderly men – from the UN”.

All this was greatly enhanced by Anna Tillbrook’s sensitive work on piano. And some of the piano writing here is complex and subtle – or witty. I loved the “knitting needle music” in Black Max, for instance.

First published by Lark Reviews: https://www.larkreviews.co.uk/?p=6701