George Bernard Shaw’s one and only foray to the southern hemisphere

Arrival

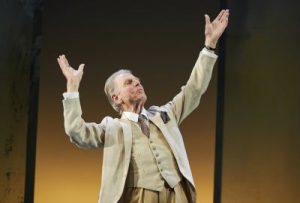

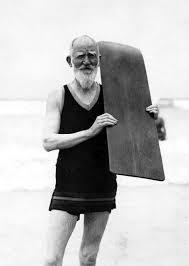

It’s a fine March day in 1935 and in Wellington, for once the leaves are still and the sun is shining warmly. A British ship has just docked and an elderly couple is processing regally down the gangway while dockers and other admirers on shore cheer wildly. He is lanky, bearded, very upright and wearing a woollen cycling suit – old fashioned even then. She is hatted and stately. They wave to their admirers.

Welcome

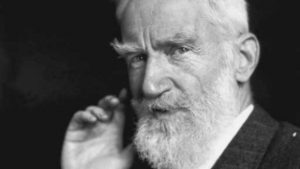

Royalty? No, not quite. This is the 78 year old George Bernard Shaw, socialist, playwright, critic, wit, vegetarian, spelling reform enthusiast and fresh air fiend, accompanied by his wife Charlotte. They are beginning their only visit to the Antipodes. So near and yet so far. They didn’t quite make Australia although they nipped round America a couple of times in 1933 and in 1936.

While in Wellington the Grand Old Man made a national broadcast with the grand title ‘Shaw speaks to the Universe’ which was also eagerly relayed across the water in Oz.

Funny family

Born in Dublin in 1856 Shaw came from a dysfunctional family which included a drunken father and a whole battery of inebriate aunts and uncles one of whom played the ophecleide (an ancient ancestor of the trombone) and repeatedly tried to commit suicide by putting a carpet bag on his head.

Eventually, the young Shaw escaped to London where his musically-inclined mother had set up home with a singing teacher, George Lee, from whom Shaw indirectly received a pretty thorough education in the subject – enough to enable him to keep himself for many years as a freelance music critic before he began writing successful plays.

Man of discipline

He also taught himself, from scratch, to play the piano – by studying the printed music and working out which keys on the piano corresponded. Who needs a piano teacher? It took him, he said many years later, ten minutes to find the first chord, but he eventually became a competent pianist able to accompany choral societies and to play informal duets with professionals. Who but Shaw could have been discovered by a friend in the British Library studying both Das Kapital, Marx’s communist textbook, and the score of Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde – at the same time?

Determination was this man’s middle name. He worked to overcome his shyness and became a fine public speaker on economics and socialism before he was 30. Having become a vegetarian when he was 25, he believed that his high energy levels came from all those healthy nuts, fruits and vegetables.

Drama

He turned to the theatre in the 1890s. Arms and the Man, The Devil’s Disciple, Caesar and Cleopatra, Man and Superman, Major Barbara and all the rest followed. They were played in New York and, in time, also in in the ‘far flung’ sunny corners of the British Empire. Shaw made a lot of money and fame became his passport. He could go wherever he liked. Everyone wanted to meet him. His original views were often highly entertaining.

Nearly turned away

The rapturous welcome in New Zealand was partly because the country had recently passed a law which meant that the government could refuse entry to any recent visitor to a communist country. Shaw had been to Russia and some New Zealanders had argued against his admittance. His arrival, he wrote gleefully, had been preceded by ‘some pretty lively press discussion as to what would happen to me.’

Give ‘em milk

Then he told socialist politicians in New Zealand – including two future Labour prime ministers – to stop acting as a dairy for the rest of the world ‘which is learning to milk its own cows.’ Instead of exporting their ‘remarkable milk supply’ New Zealand should distribute it freely, like water, to their own people. They listened. When the first Labour government came to power at the end of 1935 it gave half a pint of free pasteurised milk to every school child every day in a scheme which lasted for 30 years. Mothers wrote to Shaw to thank him. It’s not said how much the children appreciated their daily compulsory dose of the white stuff.

Touring

After a three week jaunt round North and South Island in a chauffeur-driven car, the Shaws visited a children’s hospital in Wellington where GBS enthusiastically discussed his pet topics of fresh air, light, warmth and good food with Sir Truby King, the child care expert. Lack of personal experience never daunted Shaw. A little thing like not having had children of his own was never enough to stop him from having and expressing a forthright and unorthodox view.

When Shaw and Charlotte were ready to set sail for home on board the Rangitane on 14 April, well-wishers pushed bouquets of flowers through their portholes. And no one knows whether, as legend has it, he borrowed a lady’s scarlet bathing suit and plunged into the waves at Mount Maunguni or if he really did give Auckland’s Turnbull Library a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

The end

The adventure down under was one of Shaw’s last big trips. ‘I am too old for these feats of endurance’ he said. Charlotte died in 1943. Shaw followed her in 1950 at the age of 94.They were both cremated – another of his little eccentricities – and their ashes scattered in the garden of their home at Ayot St Lawrence in Hertfordshire. The house is now owned by the National Trust and is open to the public.

Much of his fortune went in taxes but the lion’s share of what was left was willed to a movement to reform spelling . Shaw thought English spelling was absurdly complicated and he detested the apostrophe. His wishes might have been popular with English speaking school children everywhere – but they didn’t catch on.