Show: Howerd’s End

Society: West End & Fringe

Venue: THE JACK STUDIO THEATRE. 410 Brockley Road, London SE4 2DH

Credits: By Mark Farrelly. Directed by Joe Harmston.

Howerd’s End

4 stars

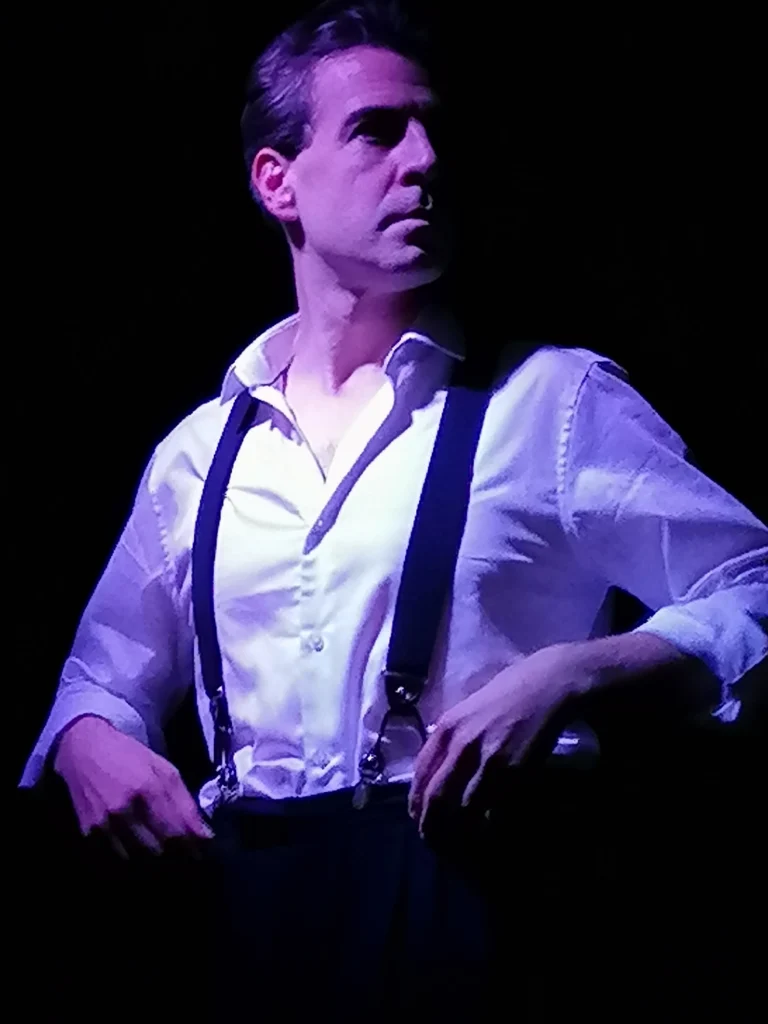

When I first saw this two-hander play eighteen months ago at the newly opened Golden Goose theatre in Camberwell, I said it deserved to get more performances. And now it’s getting them. Since then I’ve seen actor/playwright Mark Farrelly in three of his solo shows shows (one of them twice) and I’ve interviewed him so I now feel quite an affinity with his work which I didn’t have in October 2020.

The play is about Frankie Howerd (Simon Cartright) and his live-in manager/ chauffeur/ factotum Dennis Heymer. Howerd struggled with his obvious sexuality all his life and never came out as gay even after homosexuality was decriminalised in 1967. The two men were, of course, lovers in a tortured but passionate sort of way.

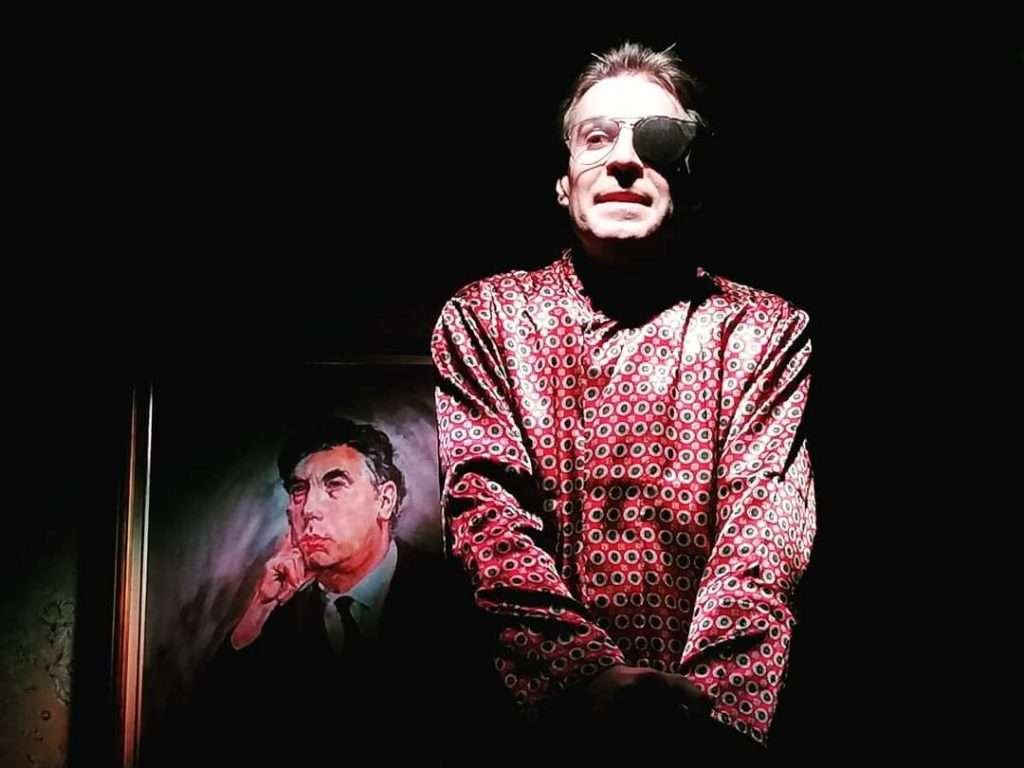

The structure of Farrelly’s play gives us Dennis, seventeen years after Howerd’s death showing a party round Wavering Down which was the latter’s Somerset home. Then Howerd (Simon Cartright – all the distinctive Howerd mannerisms deftly mastered) appears as a solid ghost to help retell the story of their life together – including Howerd’s infidelities, years in therapy, career dips and the use of LSD.

Farrelly’s Dennis is gritty but passionate, sardonically witty and skilfully nuanced. When he wants to, Farrelly can glitter with charisma and it’s very effective. The scene in which the two men first meet at the Dorchester Hotel where Dennis is working as a “sommelier” (a self-deprecatingly posh word for a barman) is funny, for example. It’s full of raised eyebrows and innuendo as Howerd gropes for secrecy and discretion but Dennis is blunt.

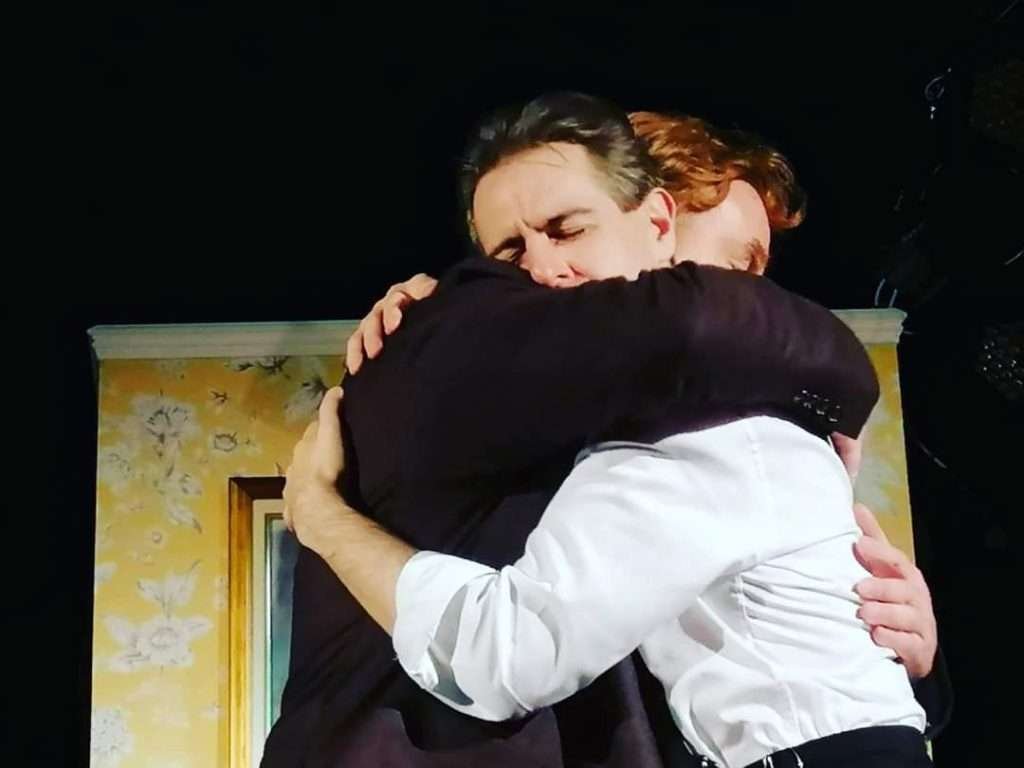

This play is a love story. Both men have imperfections and hang ups but eventually, despite everything, Howerd admits – after many rows – that he loves Dennis. Peace settles. It’s deeply moving – and intelligent. This is thoughtful theatre for grown ups.

Howerd’s End has matured since I first saw it. There’s a little more playing to and with the audience (who are meant to be the party being shown round the house) than formerly and that works well. It tours easily too because the set is only a moveable fireplace, a rug, a painting, a chair and a small ottoman. Along, with Farelly’s other plays (the rest are solo shows) Howerd’s End is popping up in a number of small theatres this spring. Definitely worth seeing.