Show: Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

Society: Cambridge Theatre Company

Venue: Great Hall at The Leys. The Fen Causeway, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire CB2 7AD

Credits: Lyrics by Tim Rice and music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, based on the character of Joseph from the Bible’s Book of Genesis. An ameatur production by arrangement with The Really Useful Group Ltd.

Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

4 stars

Rarely have I enjoyed an evening in the theatre so unequivocally. The warmly familiar show itself packs more smile-factor than almost anything else I can think of. And CTC’s practice of using its vibrant, enthusiastic, talented youth theatre alongside very competent non-professional adults works a treat.

Director/Choreographer. Chris Cuming. sets the show in a school library with primary school children reading books so the set is a bit Matilda-like but it’s an inspired idea. The children and teachers are re-enacting the story of Joseph in assembly so the headmaster becomes Jacob, the PE teacher becomes Pharaoh and other roles emerge from the community. As the story starts we move from grey school uniforms into colour (costumes by Liz Milway). And it works splendidly; fizzing with visual and aural energy throughout.

Vikki Jones is outstanding as the teacher/narrator, holding the book she’s pretending to read from, “directing” her charges, singing and dancing well and making it all look smilingly, professionally effortless.

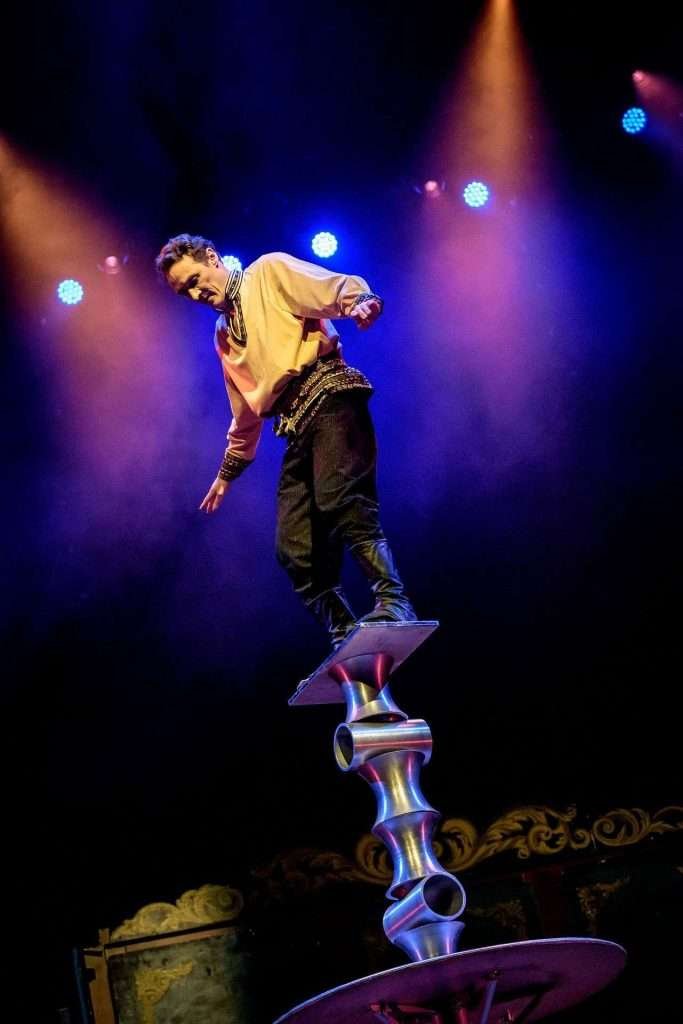

Ben Lewis, initially a puzzled bespectacled teenager in his school tie, morphs into a charismatic and ultimately authoritative Joseph and sings with maturity. Rodger Lloyd has enormous fun with the Elvis/Pharaoh number gyrating his hips and pointing at women in the front row and Lake Falconer finds gentle gravitas in Jacob.

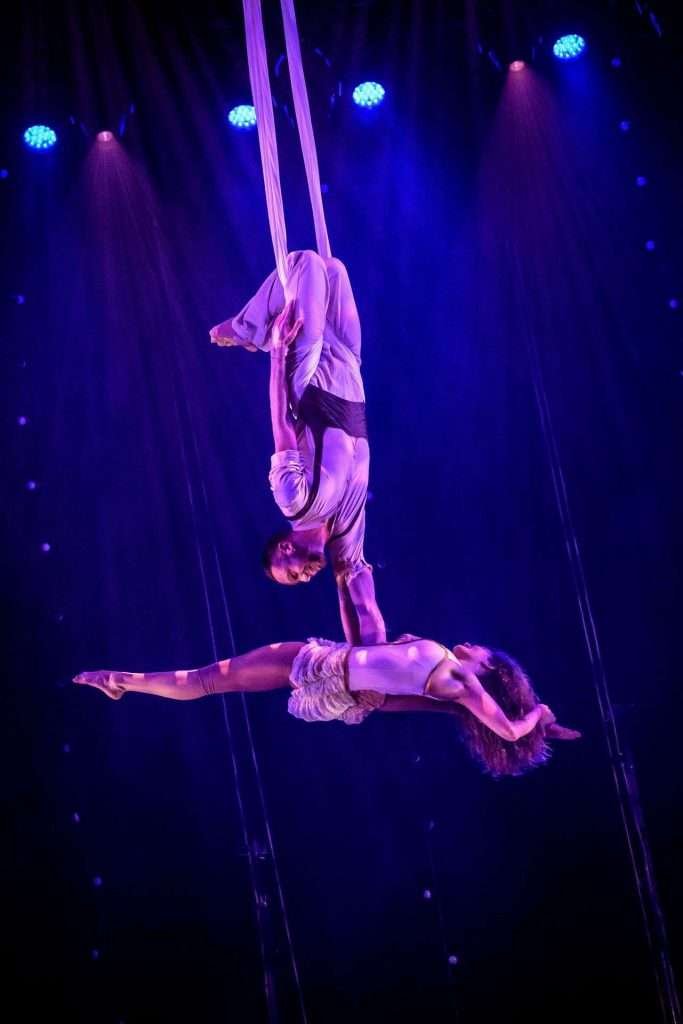

But the real star of the show is the ensemble which moves continuously with volumes of slick, well disciplined exuberance. Cuming really knows how to get the very best from them. Even the finale/curtain call is a choreographic gem. And let’s hear it too for Jennifer Edmonds’s eight piece band on a high platform at right angles to stage right. Lovely clarinet work from Graham Dolby and I know the xylophone in “Any Dream Will Do” is just a key board switch but it sounds great.

Of course it wasn’t perfect – there was the occasional bum note and missed entry. This was the opening night after all. A superb achievement, though, by any standards.

I couldn’t help comparing this show with my disappointing 2019 experience of seeing the much hyped version with Sheridan Smith, Jason Donovan and Jake Yarrow which I found forced and oddly unengaging. CTC’s lively, imaginative show is anything but and I know which version I much preferred. Thank you, CTC. This was just what I needed just before Christmas and a real antidote to some of the lacklustre pro shows I’ve seen in recent weeks.

First published by Sardines: https://www.sardinesmagazine.co.uk/review/joseph-and-the-amazing-technicolor-dreamcoat-12/

- All photos: Eliza Wilmot